Remembering January 26

Australia Day on the 26 January has become such a major event in our national calendar that it is easy to forget that the name of this public holiday is relatively recent. The day is historically significant, of course, as the anniversary of raising the Union flag in Sydney Cove on the 26 January 1788 after the arrival of the eleven ships of the First Fleet in the harbour. A contemporary description of the event suggests it was a fairly low-key affair:

In the evening of the 26th the colours were displayed on shore, and the Governor, with several of his principal officers and others, assembled round the flagstaff, drank the King’s health, and success to the settlement, with all that display of form which on such occasions is esteemed propitious, because it enlivens the spirits, and fills the imagination with pleasing presages.[i]

It had been a big day during which the two ships of the French explorer La Perouse were sighted offshore as Captain Hunter in the Sirius led the fleet of transports and store ships out of Botany Bay to Port Jackson where Governor Phillip had sailed ahead in the Supply. The arrival of the French was a complete surprise and probably uppermost in Phillip’s mind, but in the circumstances their presence must have added impetus for the flag raising ceremony, a symbolic reaffirmation of Cook’s 1770 claim of the east coast (New South Wales) of the land named by the Dutch, New Holland, over a century earlier.

Early colonial references to celebrations in January often refer to the Queen’s Birthday anniversary. For example, the Government Order for 18 January 1803 stated:

This being the anniversary of Her Majesty’s birthday, Lieutenant-Colonel Paterson will direct the quartermaster to draw a proportion of fresh beef from Government House, to furnish a pound to each non-commissioned officer and private of the guard on duty at headquarters.[ii]

Until the later years of the 19th century, individual colonies generally celebrated dates important to their own foundation and tended to look on the 26 January as a singularly New South Wales anniversary. By 1888 however, on the centenary of British settlement, when representatives from each colonial government in Australia joined Lord Carrington, the New South Wales Governor in Sydney for the occasion, there was growing acceptance that the date was of national significance, although it continued to be known as Anniversary Day.

Tall ship First Fleet re-enactment on Sydney Harbour, Australia Day, 1988. The Australian Bicentenary was marked with much ceremony across Australia. Australian Overseas Information Service - National Archives of Australia, via Wikimedia.

The Bicentenary

General support for the name Australia Day really only developed in the lead up to the 1988 Bicentenary, and national events on 26 January 1988 were of such magnitude, that the name is now firmly established. In his Australia Day speech Prime Minister Bob Hawke noted the importance, when celebrating the nation’s present and future, of remembering:

‘…what we owe to the people who have been before us – the Aboriginals who have lived on this continent for some 40,000 years, those who settled Australia in 1788, and those who have made Australia the home of their choice since then.’

Those three strands remain integral parts of the national fabric and today, Australia Day has become the most important anniversary in the national calendar, a powerful symbol of nationhood, and inevitably, a focus for widely divergent attitudes. Striking a balance between national unity and cultural diversity that appropriately recognises and respects Indigenous, colonial and migrant heritage but also looks to the future, remains a challenge, but one we should look toward with confidence.

Some people will be surprised to learn that historically, 26 January is also significant as the date marking the only military overthrow of government authority in Australia.

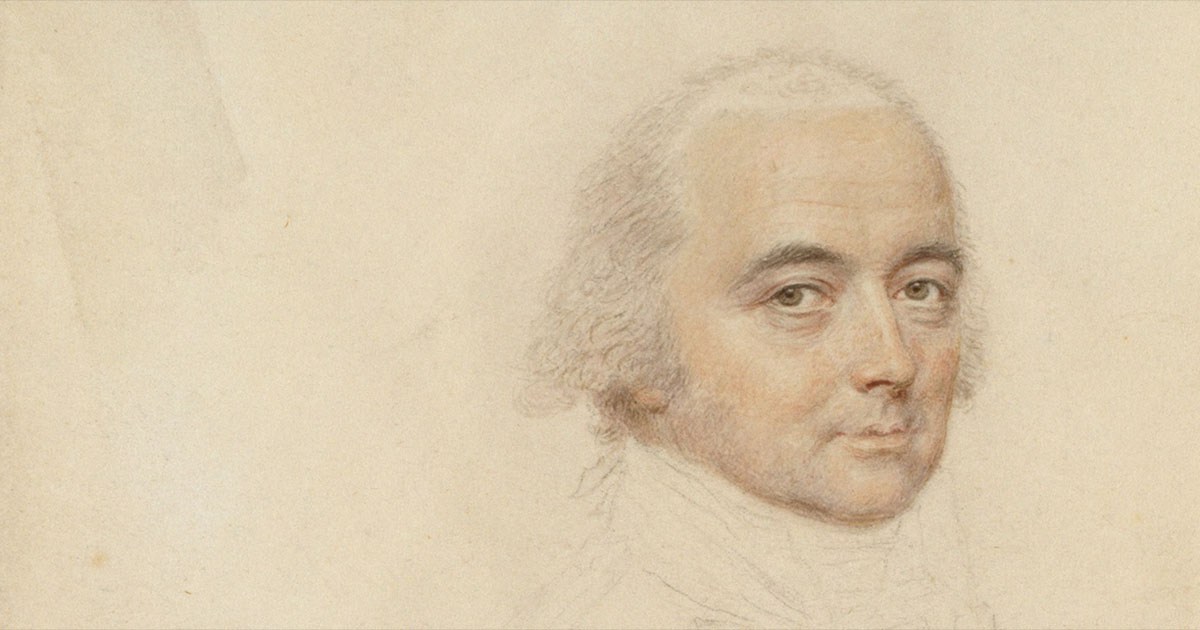

This painting of William Bligh by Helen S Tiernan is based on a 1776 portrait by John Webber. William Bligh, a contentious figure in both British and Australian history, was the fourth Governor of New South Wales. Bligh arrived in the colony in August 1806 but in January 1808 was arrested and overthrown by the military during what became known as the Rum Rebellion. Bligh fled to Hobart and although the military action would later be ruled illegal in London courts, Bligh never returned as Governor. ANMM Collection 00055148.

The Rum Rebellion

Now known as the Rum Rebellion, on 26 January 1808, the soldiers of the New South Wales Corps marched with fixed bayonets through the streets of Sydney under the command of Major George Johnston to Government House where they arrested Governor William Bligh. Many people will remember Bligh from movies as the tyrannical captain of the Bounty who drove his men to mutiny, and throughout his career Bligh’s character was the subject of contention and debate.

In fact, he had been selected for the post of Governor of New South Wales, largely because of his reputation for firm discipline, to curb the power and corrupt practices of the News South Wales Corps and some private individuals in the colony.

Kept under house arrest until he escaped and sailed to the Derwent, Bligh was not reinstated to his authority until the arrival of Lachlan Macquarie in 1810, when after a brief official recognition, Macquarie relieved Bligh as Governor. Bligh then returned to London where he was later present at the court martial of George Johnston, now promoted Colonel. In his defence Colonel Johnston produced a document signed by many individuals in Sydney which he claimed as evidence of the widespread alarm and chaos rampant during Bligh’s administration, and the justification for his extraordinary actions. Unhappily for Colonel Johnston, it didn’t convince anyone and he was duly cashiered from the army!

26 January 1808 was certainly not a happy day for William Bligh but was he responsible for chaos in the colony? Was he just doing his duty? Was it just another example of the spectre of the Bounty mutiny returning to haunt him?

These are just some of the questions raised in the examination of William Bligh’s tempestuous career to be considered in the museum’s upcoming winter 2019 exhibition Bligh: - Hero or Villian?

Sources

[i] The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, Stockdale, London 1789

[ii] Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. 6