What people did on long sea voyages

In my first week of volunteering for the Vaughan Evans Library, I got to read several journals made by people traveling to Australia in the 1800s – mostly passengers, with a captain’s diary as an exception. Some of them are fun, some are wistful, and some are both at once: pigs and captains falling overboard, total eclipses and peculiar fish, missing home and family. It's strange to sit behind a library desk and see into someone's personal thoughts, hopes, fears, and dreams, while knowing that the author is long dead.

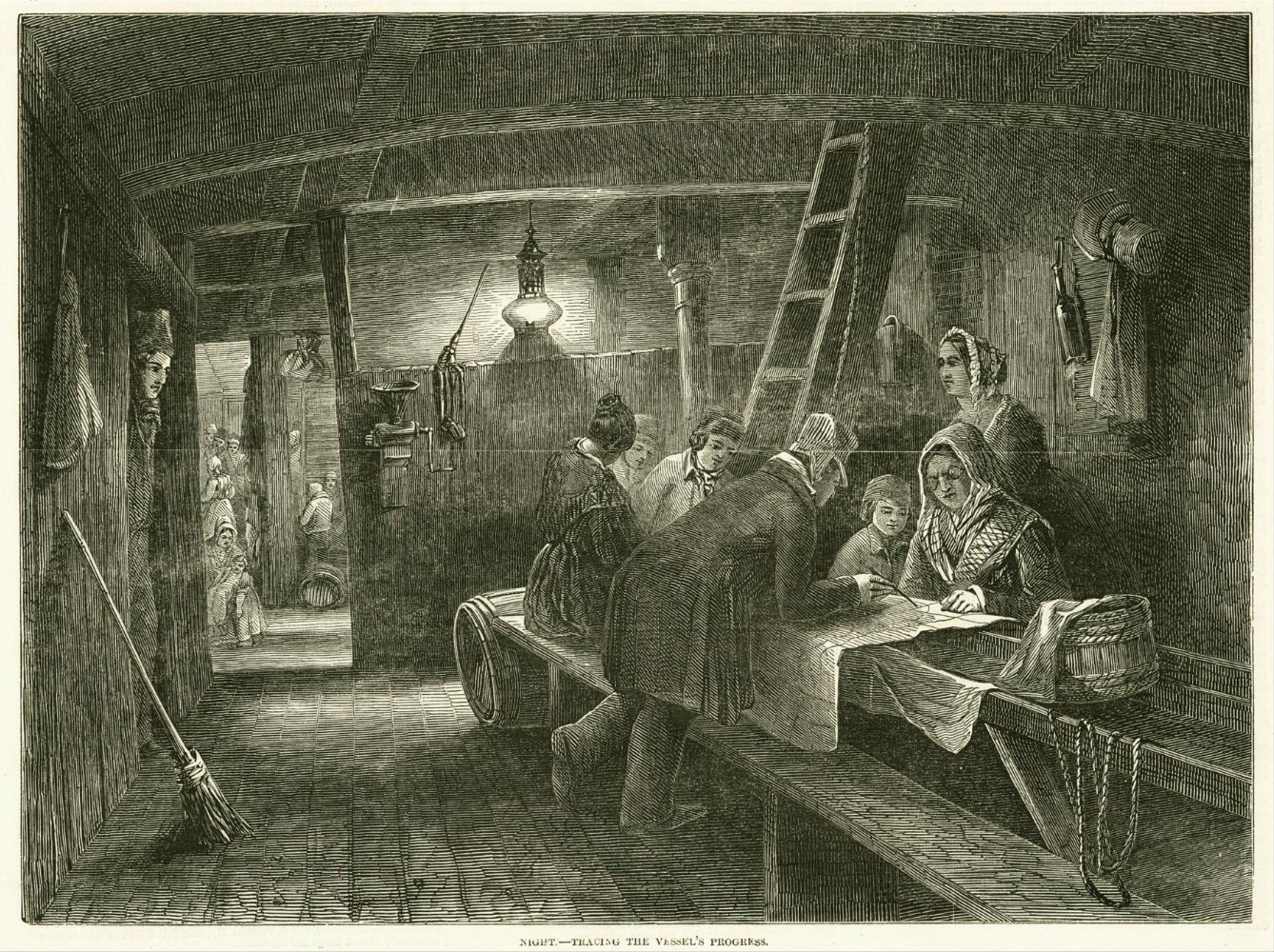

Most of the people whose diaries and journals I read had never been on a ship, and certainly never had to deal with the dullness that most passengers of a sailing ship were subject to during journeys from Europe and America to Australia: several months of confined quarters, other passengers and the crew as the only company available, sailing into the unknown. Despite this, they still found different ways to amuse themselves, some of which were quite surprising!

The authors

Mrs. Pexton is traveling to New South Wales and then to India on board the Pilot in 1816-18. She travels with her husband, who is the captain of the Pilot. She doesn’t like Sydney, but loves Australian animals and keeps some of them as pets when aboard.

Eliza Taylor, is traveling from England to Sydney in 1833-34. Eliza enjoys observing the stars and the fish, and gets truly poetic when describing the sea. She is also prone to occasional melancholy.

Francis Gosling, is going from London to Sydney on board of the Alexander in 1835. Francis dedicates his journal to his father, whom he had to leave behind in England and whom he now misses very much: he mentions how much he regrets his father's absence all the time.

David Melville, is a clerk traveling to Australia on the North Briton in 1838-39. His writing is beautiful, especially when he talks about animals, and he seems to be very depressed about leaving his home and loved ones – so depressed I actually got concerned about the man. He will settle down in Sydney, get married, and die at the age of 66. I hope he found some peace on these shores.

Another passenger of the North Briton on the same voyage as David is John Sceales, who likes to gossip about his fellow passengers and records his opinions in his journal better than your average Twitter user.

Joseph Price’s journal of the voyage on the emigrant ship Confiance from Liverpool to Geelong in 1852 features his own account (he was the captain) and several passengers’ diary entries. The trip was grim and dangerous, with an epidemic of dysentery and a lot of infant deaths on board, but there still are some fun things the authors found to amuse themselves with.

And finally, Edward Roper, is traveling on the Concordia from Boston, in the United States, to Australia in 1852-53. Edward is an artist, and his journal features several drawings of the fish, birds, and the islands he spots in the distance. He also takes up tattooing during the journey.

On nautical astronomy and the celestial globe, from A Compendium of the Art of Navigation, by John Edmund Ludlow, 1819. ANMM Collection 00040486.

Eliza is not the only passenger eager to learn their way around altitudes: Simon Morrison, a passenger on Confiance, is equally proud to learn to use the sextant; he can now “take altitudes of the sun and moon with great ease and exactness” almost as well as the ship’s captain, as he confesses in his journal.

Sextant made by Spencer, Browning and Rust, 1784-1840. Simon would have learned how to use a similar one. ANMM Collection 00006886. Purchased with USA Bicentennial Gift funds.

In the same manner that Eliza is inspired to wake up early to witness the sunrise, Simon goes on deck at night “to stare at the Southern heavens”. Amazed by the sight of the Milky Way’s expanse, he concludes: “No wonder that Sir John Herschell said it looked like gold dust scattered on the background of the heavens." David Melville does the same: in his diary he describes sitting on a taffrail for hours, gazing on the deep in the clear moonlight. Eliza, Simon, and David all stared at the same stars, years between their journeys dividing them, similar routes of their vessels connecting them – and the rest of humanity - through centuries of fascination with the night sky.

Another peculiar thing Eliza gets to witness is the total lunar eclipse of 1833, which took place in most parts of the southern hemisphere on December 26 and lasted as long as Eliza described in her journal: a little more than three hours, starting at 7pm in the evening and going on past 10 o’clock that night. William Pinnock’s The Guide to Knowledge, a book on arts and natural curiosities published in 1833, enthusiastically advised its readers not to miss this eclipse, and provided a picture explaining the mechanism behind it:

W. Edwards, J.B. Gilbert, and W. Pinnock, The Guide to Knowledge, v. 1 (1833).

Dance and song

Dancing in the evening was usually an opportunity for the passengers to mingle, get to know each other, and just have fun. Several diaries mention dancing lasting long into the night, sometimes until 1 or 2 AM, with some of the crew members joining when they could (usually after the crossing of the Line ceremony, when the captain would allow for the crew to drink, rest, and dance). Some passengers could play musical instruments, such as fiddles or flutes; others were good singers, coming together on the poop deck to sing while their audience listened. The sailors sang as well, assembling on the forecastle, the crew’s usual communal space, and their foc’s’le songs could be heard by the passengers, such as John Sceales: “I went into the forecastle and heard some songs from the sailors”.

Dances mark all sorts of occasions, such as the crossing of the Line ceremony, Christmas, the Captain’s birthday, or New Year: on 31 December 1833, Eliza, in a charming turn of phrase, dances “the Old Year out” with the captain, and the New Year in with another passenger, dancing until two in the morning. In twenty years, Edward Roper will see the old year of 1852 out the same way, dancing between decks until midnight, until everyone goes on deck and welcomes 1853 with “guns, bells, voices and pistols”. On Christmas Eve Eliza dances all the evening as well. The Crossing of the Line ceremony -- an old tradition celebrated upon a vessel crossing the Equator -- usually wrapped up with dances and sailors singing songs such as “Hearts of Oak” or “Bay of Biscay”, and Francis Gosling gets to dance with the boatswain – “a very pleasant man”.

However, dances didn’t always need a special occasion: they were for amusement, fun, and socializing. John Sceales mentions a social party with all the passengers “with songs, Toasts, [and] speeches” starting below deck and continuing on the main deck in the darkness, where John played his “little flute” and most of the men passengers danced “with great pleasure”. As John doesn’t mention any ladies joining them, we can assume the men danced with each other.

Mazurkas, Quadrilles, Country and “Scotch” dances seem to be the most popular styles aboard during this time, and usually happen in the evening when the day's work is done, lasting long after midnight - though on Confiance the ladies would be asked to go their bunks at eight in the evening, and the gentlemen were allowed to remain until nine. Eliza is luckier: she often mentions dancing until midnight, or “all the evening”, though I suppose the New Year’s party until 2 AM was a special occasion.

Strange new animals

Compared to the usual fauna that the passengers knew from home, even seagulls were a novelty to some, let alone strange fish or, even more exotic, jelly-fish. Decade after decade, people continue to be amazed by the creatures they encounter on the same route: Mrs. Pexton is just as amused by Portuguese men-of-war in 1816 as David Melville in 1838, and porpoises are a constant playful presence year after year in every single journal.

Trying to describe the animals in their journals and letters back home, passengers used terms familiar to them: seagulls are described as pigeons that make duck noises, flying fish "look like golden mackerel", Boneta fish resemble veal when cooked and the pilot fish is striped like a zebra -- it's curious how a zebra is now a more or less known animal for Eliza, a lady from Gravesend. Francis Gosling compares an albatross to a pigeon, too, though I don’t know why he would find them alike. Francis, what kind of pigeons have you met before?

Edward Roper’s take on what he believes to be a dolphin and a rudderfish (a black ruff):

From Edward Roper’s ‘Journal of the voyage of the ship Concordia from Boston, United States to Australia in the years 1852 & 1853’, Vaughan Evans Library, ANMM.

Fishing was a common pastime, either for fun or to eat the caught fish later, with examining it first always essential. Poor sharks however were often hunted out of sheer hostility for their kind, and David Melville calls them “great lazy horrid looking devils”. After one of the crew members falls overboard David supposes that the sharks would probably finish him. Eliza Taylor, meanwhile, eagerly awaits for a shark to be caught so that she’d have “6 of his teeth, to send to England”, as promised by the captain. Bonito fish, dolphins, and porpoises are spotted often as well, the bonito usually caught for food. Francis Gosling is often amused at the porpoises jumping in and out of the water, and once the sailors on his ship harpoon one of them, they casually throw it back into the sea after taking a full view of it. Porpoises play around the Confiance to the joy of its passengers, who call them sea horses or sea cows, and on the North Briton some mistake them for sharks while they follow the vessel -- as David Melville writes, there’s a great fright because of the old superstition that “they never follow a vessel but when someone on board is about to trip anchor”, that is, to die.

Eliza Taylor, meanwhile, is told they can’t remain inactive in the water without sinking. She seems very excited about marine fauna: she calls the Portuguese man o’ war’s sails “magnificent”, but she is disappointed that they dissipate into nothing when taken out of the water. She is very interested in the flying fish's scales, "a curious object for the Microscope", determined to bring some of the fish back home. Eliza even willingly touches the man o'war after her fellow passenger Mr. Allen suggests that "all naturalists must experience the sting of the little purple nail" to be able to describe the pain later! She cures the large white blisters on her hand with lime juice. Mrs. Pexton spots the man o'war too, and David Melville sees "immense numbers" of them, "their tiny sails stretched to the breeze”.

Engravings of molluscs and zoophytes by Charles Alexandre Lesueur, 1807. Physalia on the far left is a genus that includes the Portuguese man o’war, which our diary authors would see in abundance during their journeys. ANMM Collection 00004303.

David Melville is especially eloquent in describing whales: “unwieldy and of course not by any means beautiful, [a whale is] still one of the monsters of the deep and we stared at him accordingly which did not seem to give him the slightest disturbance”. When seeing a whole group in the distance: “They, however, have not condescended to shew their carcasses – probably they suspect us of wishing to make a tangible acquaintance with them”. Meaning, to kill them.

Though marine customs prohibited killing seabirds (albatrosses in particular, lest bad luck would be brought upon the vessel), most of the diaries mention catching the birds to either stuff or eat them. Francis gets to share a cape pigeon and an albatross with the ship’s surgeon, and as they’ve only got one knife, Francis eats with his hands and finds it very funny. Eliza Taylor mentions catching an albatross and letting him go, to the disappointment of the midshipmen who were ready to make it into a pie. Aboard the Confiance, a curious thing happens: a caught albatross has a ribbon on its neck, showing that it had already been captured and let go by someone before. The captain binds another ribbon with "Confiance" written on it around the bird's neck and sets it free. Imagine the albatross’ frustration - yet another scarf!

Edward Roper strikes again: an albatross, a mollymawk, and several cape pigeons.

A page from Edward Roper’s ‘Journal of the voyage of the ship Concordia from Boston, United States to Australia in the years 1852 & 1853’, Vaughan Evans Library, ANMM.

Drawing, writing, reading

Edward Roper is hands down the leading artist in this hand-picked group of diarists. It's not surprising, as he's not an amateur sketcher but a painter, illustrator, and lithographer, and had studied art in Paris. The man is relentless: aside from drawing animals, islands, and towns, he is also commissioned to do several drawings of the Concordia by the ship’s captain. He also sketches a passing Scottish ship Jane Erwing, draws a vessel for one of the sailors and a portrait of the ship’s third mate (which turns out “better than I could expect”), paints the capstan, prints names on people’s trunks, and engraves “the Maid of Saragoza from Byrons works” -- Agustina de Aragón, a Spanish Peninsular War heroine, about whom Lord Byron wrote in Childe Harold -- on a piece of charred wood. He also takes up tattooing on men’s arms during the journey, so here is a list of the designs he mentions:

- Topsail schooner (x2)

- A brig (x2)

- An anchor (x2, one of them on himself)

- Various people’s initials (C.W., D.D., etc)

- A soldier holding a British Jack

- A barque and a British Jack

- The Isle of St Helena (Edward specifies that this was tattooed on a Frenchman. I’m guessing that the French passenger wanted to honour Napoleon Bonaparte’s memory with it)

- A horse

- A hunter with a dog

- A rose

- The Royal Arms of England (“This is the best I have done”, he proudly concludes)

Aside from Edward, Eliza Taylor leaves several drawings of her surroundings as well, all pencil drawings with minimal details: Cape of Good Hope, Peak of Tenerife, Cape Town. She had also preserved a fibre of corn “of which the ancients made paper”.

![Eliza Taylor. Peak of Teneriffe [sic] 5 Miles distant. ANMM Collection 00036438.](/-/media/anmm/images/blog-content/2019/01-jan-2019/of-stars-and-jellyfish_crop.jpg?la=en)

Eliza Taylor. Peak of Teneriffe [sic] 5 Miles distant. ANMM Collection 00036438.

Another activity to pass the time was writing long letters to loved ones at home, which would be passed on to a homeward-bound ship met along the route. It was the only comfort for those passengers who missed their families, such as Francis Gosling, who is very anxious about never seeing his father again, or David Melville, who has similar fears: "Oh God what would I not give to clasp you all to my heart again and shall it ever be?" he writes.

People read avidly as well. David seems to have a liking for Romantics (which also explains his writing style, sometimes very dramatic): he reads Percy Shelley’s “Queen Mab” and Byron for hours “to [his] great delight”. After finding on board the North Briton a book by Edward John Trelawny that he couldn’t find in several libraries in Edinburgh, he’s so happy he hugs the volume. Meanwhile, Francis Gosling reads religious works such as Thomas Scott’s “The Force of Truth”, part of the library that his father gave him for the journey.

Other pastimes

Drawn to each other's’ company, the passengers came up with other group activities, such as assembling on deck for a game of chess or draughts, card games such as whist, backgammon, and cribbage. Francis Gosling in particular plays cards often, but always "for love", without any bets - and he often wins, boasting that he's "always a lucky dog", adding in his diary that the reader may imagine his opponent’s anger. On the North Briton, cabin gentry boxes and wrestles, and David Melville mentions sticking bottles up the lower studding-sail boom and shooting at them for fun. On Valentine's Day (February 14th) the single women of the Confiance exchange love letters with the sailors, and earlier in December a school is organized for the emigrant children, where Simon Morrison distributes books and forms the kids into classes.

Sudden and strange events amuse the audience to no end, too. Francis gets to see a pig fall overboard, and despite all attempts to rescue the poor animal, it swims around the ship two or three times “making a most horrible noise” and dies. Francis concludes that he had never laughed so much as he did on that evening. Francis also gets to see is the ship’s surgeon overdosing on laudanum, which he used as a painkiller for his toothache, and threatening to shoot everyone on the deck in his delirium; fortunately, he feels better after a good night’s sleep.

A lot has been left out of this collection of accounts: thoughts of people longing for home, dreams (nightmares about dental problems seem to be universal over centuries), fresh gossip from the 1850s. I found them all very lovely, and feel as if I got to know this bunch of people in real life, even if for a couple of weeks.

Alex Murtazaeva, Volunteer researcher.

Sources

- Journal of a voyage from England to Sydney New South Wales [manuscript], by Eliza Taylor. Diary written on a voyage from Gravesend to Sydney 1833-1834.

- Account of a voyage on board the ship Pilot, Captain Wm. Pexton to Port Jackson New South Wales from thence to India [manuscript], by Mrs Pexton. 1816-18.

- Journal of the voyage of the ship Concordia from Boston, United States to Australia in the years 1852 & 1853 [manuscript] : also comprising a stay in Australia at the mines & in town / by Edward Roper.

- Manuscript diary [manuscript]: journal of a voyage from London to Sydney on board the Alexander, Francis Gosling. 1835.

- The voyages of Joseph Price from 1829 to 1854 [manuscript] including the voyage of the emigrant ship Confiance from Liverpool, December 1852 to Geelong, Victoria, Australia, April 1853 and the return to England, June 1854 / by Joseph Price ... [et al.], Vaughan Evans Library, ANMM.

- 35th Voyage in the Ship “Confiance” from Liverpool, December 1852 to Geelong, Victoria, Australia, April 1853, carrying government assisted emigrants, thence to Peru and the return to England. (Several authors)

- The ship "North Briton' : voyage to Australia 1838/39. The diary of David Melville, presented by Juanita Minter. 1992.

- Steerage to Australia : a diary of John Sceales voyage on the "North Briton" 1838/39, John Sceales; presented by Juanita Minter.