Kalwa and Walba: Two rafts

Aboriginal rafts have always co-existed alongside Aboriginal bark canoes, and a raft structure may be the type that originally brought people to Australia more than 50,000 years ago. They may then have been the first type of craft used to exploit waterways as people settled around the country.

Aboriginal rafts have co-existed alongside bark canoes.

The museum has two examples from different northern communities, a kalwa and a walba, and they represent a navigable version of a raft, a term often reserved for a floating vessel that drifts with the tide and wind. In that situation a raft is a buoyant apparatus or platform and not much more, stable enough to fit and support a load on its top surface. However many of the Australian types were capable of controlled navigation rather than just drifting with current, tide and wind.

A successful raft firstly has sufficient volume to support its load, and this is largely achieved by using a light-density material. Securing this together as a rigid structure is the next important requirement. The final element that transforms many rafts into a navigable boat is the shaping.

Rafts from the Kimberley coastline

Perhaps the best-known Aboriginal rafts are those from the King Sound region of the Kimberleys in Western Australia. The Bardi community from the One Arm Point region term use the term kalwa for the raft, but the same type is also known as a kawlum by the Worora community from the Collier Bay region further north and biel biel by the Djawi community.

An experienced Bardi elder made the museum’s kalwa in 1986. He passed away recently and, as is custom, the community does not refer to his name. The kalwawas purchased through the Goolarabooloo Aboriginal Arts and Craft Shop, Broome, WA.

The Kimberley region is renowned for its rugged terrain and harsh environment, and the waterways mirror this with their strong tides, whirlpools and rips creating difficult passages, alongside areas of calm water in the many bays.

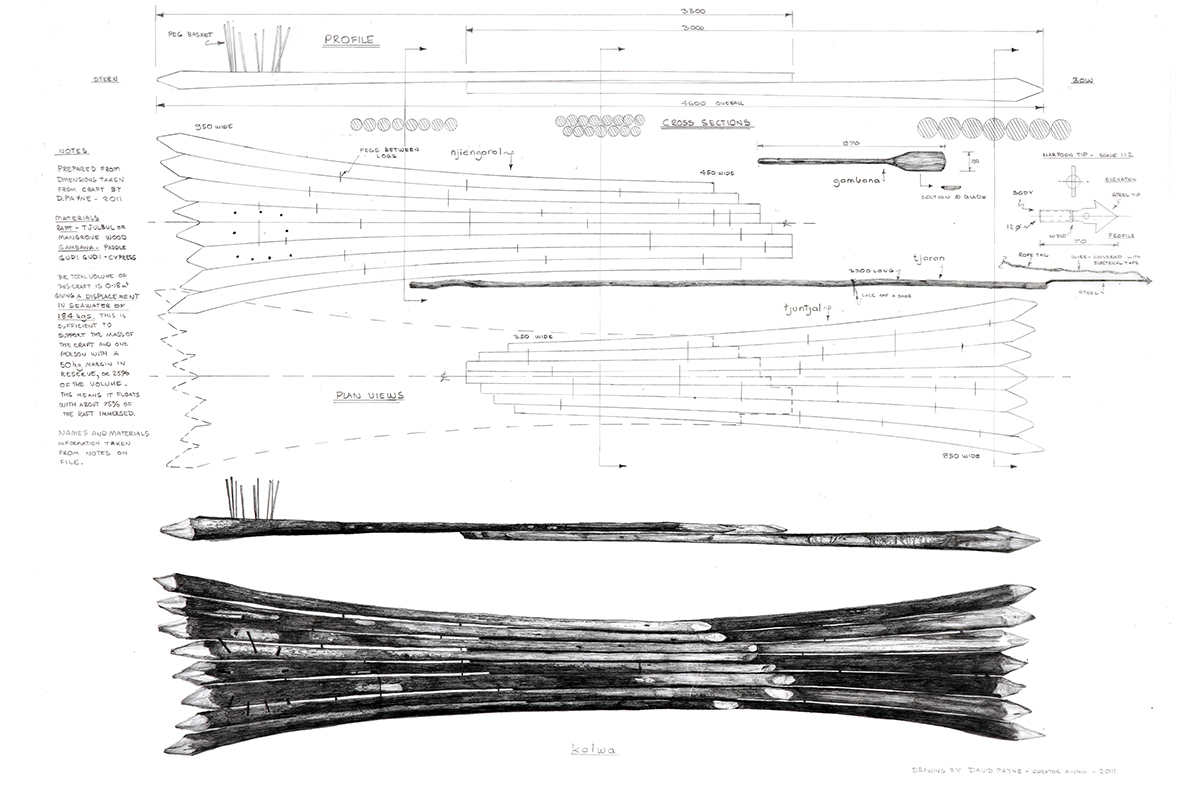

The kalwa is a double raft made of two fan-shaped sections that are lapped one atop the other. Sharpened mangrove-wood trunks form their base, then they are pinned together with hardwood pegs, the raft’s tapered fingers forming an elongated shape, with the wider ends forming the bow and stern of the double raft. A small basket was formed with pegs on the stern section to secure belongings or fish that were caught. A paddle and a harpoon and tip were made to go with the museum’s kalwa .

Kalwa.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00001700.

Kalwa.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00001700.

The Kimberley region is renowned for its rugged terrain and harsh environment, and the waterways mirror this with their strong tides, whirlpools and rips creating difficult passages, alongside areas of calm water in the many bays. The arrangement of pegs tying the rafts together creates a strong structure that is quite capable in these conditions.

Kalwa.Image: Andrew Frolows / ANMM Collection 00001700.

Kalwa.Image: Andrew Frolows / ANMM Collection 00001700.

Buoyancy is the critical area to satisfy, and only light materials will allow enough reserve volume above the line where the raft floats to accommodate the added weight of a paddler, passengers and belongings. The water can wash through the open structure as well, and the thicker and much wider ends provide the necessary stability. Seated midway along and using a long-handled paddle, with a harpoon at hand, the Bardi fisher would search ahead for signs of dugong or turtle. The two-part structure could come in half if needed when hunting dugong. The harpooned animal was tied off to one half and allowed to swim around until it became exhausted.

Rafts from the Wellesley Islands in the Gulf of Carpentaria

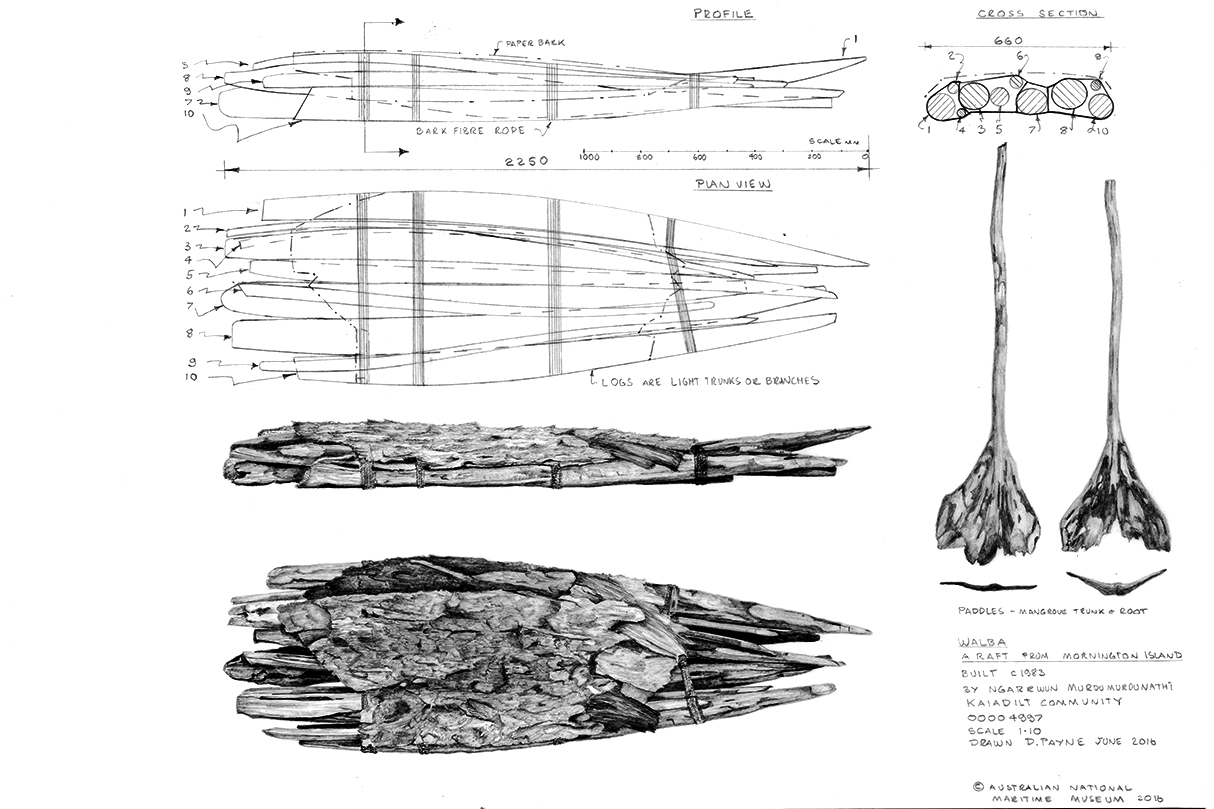

In the relative calm and shallow waters of the lower Gulf of Carpentaria are found the distinctly V-shaped walba, walpa and walpo types of raft from the Kaiadilt and Lardil communities on the Wellesley Islands. These are made from logs and branches that are bound together and finished off with a paperbark or grass platform. They were used for hunting dugong and turtle and crossing some of the waterways between islands.

Ngarrawurn Murdumurdunathi from the Kaiadilt people made the walba that came into the museum collection in 1987. It was purchased through the Muyinda Aboriginal Corporation on Mornington Island, Qld.

Walba.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00004997.

Walba.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00004997.

These craft are also reliant on lighter-density material. Placing larger diameter pieces in logical locations on the side and base provides a good framework for smaller diameter pieces to be used in conjunction, so that overall the raft has sufficient strength when tied together. Here two things seem paramount: a good tight fit between the limbs used, with some overlapping and intertwining an advantage, along with a tight, well secured series of ties across the craft.

The tiny vessel was used to venture across a river or close to shore, to fish on reefs and even hunt for dugong with a net.

The walba has a finer end at the bow, where the maker has carved the branch ends smooth and sharp, then knitting all the logs tightly together with strong handmade hibiscus rope.

The tiny vessel was used to venture across a river or close to shore, to fish on reefs and even hunt for dugong with a net. A carpet of flaking hibiscus bark or paperbark sheets lies over a seemingly random tangle of white mangrove branches, whose intermingled twists and turns camouflage the considered layering, binding and shaping that underpin the structure. The walba has a naturally shaped paddle made from the mangrove tree’s buttressed root, and two examples came with the walba.

Walba. Image: Andrew Frolows / ANMM Collection 00004997.

Stern of the Walba. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00004997.

The walpo is a much bigger and longer version, but is made in much the same way. As with the kalwa the water and waves can wash through the craft but if the reserve volume is sufficient it will sit with enough height above the water for the paddler. Stability is difficult, as there is little reserve material at the sides to take up volume as it heels over. So care needs to be taken, but an experienced person will know the limits and maintain the best position at all times.