New South Wales hosts a wide variety of historic shipwreck sites. These range from large, fully exposed and intact hulls to smaller, largely disarticulated, dispersed, and buried structural components and artefacts. The environments in which these sites exist also differ significantly in terms of seabed composition, water depth and water clarity.

Many historic shipwrecks in New South Wales waters are located at depths near or in excess of 20 metres (66 feet) and are characterised by moderate-to-low visibility conditions. These attributes in turn often negatively influence working conditions, particularly the amount of time available to execute an adequately comprehensive documentation program.

As Dr James Hunter recently discussed in his blog Meanderings in the Murk: Diving on the wreck of the Centennial, the use of 3D mapping software such as AgiSoft Photoscan and small compact underwater digital cameras such as the GoPro to document and analyse submerged archaeological sites is an emerging field of research in maritime archaeology.

Although digital photogrammetry has rapidly evolved into a relatively inexpensive and efficient means of documenting submerged shipwreck sites, it is still fraught with issues and in-water survey methods still need significant refinement in order to produce the most time and cost efficient results. In an effort to test the efficiency of these methods as a mapping tool maritime archaeologists at the museum’s Maritime Archaeology Research Centre (MARC) and the Silentworld Foundation have selected five shipwrecks in New South Wales waters with diverse site and environmental profiles.

These include the composite-hulled sailing ship Centurion (1887), the paddle steamer Herald (1884), the screw steamship Royal Shepherd (1890), the iron-hulled steamship Centennial (1889) and the iron-hulled steamship SS Lady Darling, which was wrecked south of Montague Island off Narooma, New South Wales, in 1880.

The Lady Darling

The SS Lady Darling was a single screw, iron-hulled, wooden decked, three-masted, brigantine rigged, auxiliary steamer. It was built by W.H. Potter and Company in Liverpool, England in 1863 and launched in July 1864. The steamer originally displaced 649 tons (net) and was 73.03m (189.7ft) long, had a breadth of 8.83m (28.10ft) and was powered by a 100 horsepower, twin cylinder steam engine.

It had an elliptical counter stern, four iron bulkheads and was strengthened along its lower hull with concrete. It was originally registered in Liverpool, England (Liverpool 426/ 1864), its official number was 50499 and having been built under a Special Survey was classified A1 by Lloyds in 1864 (Smith and Nutley, 1998).

The vessel arrived in Melbourne in January 1865 and its registry was transferred shortly afterwards to Melbourne in 1866 (Melbourne 9/1866) with its owner recorded as Charles Edward Bright (Bright Brothers and Company) of Melbourne. In November 1866 the vessel was laid upon the Government patent Slip where the hull was painted, its bottom coated with Borthwick’s Patent Anti-fouling Composition and its compass adjusted.

The vessel then commenced operations as a collier (general cargo carrier) and following a refit, a coastal passenger vessel on the Melbourne to Newcastle via Sydney route. Given the tough competition of the route, the vessel was not a success and was subsequently sent back to England. Lady Darling’s registry was transferred back to Tyndall and Heywood Bright, of Liverpool, in 1869.

Back in Liverpool, significant structural modifications were made to the vessel in 1870. These included lengthening the vessel by 50 feet to 239.5’ (72.9m) as well as adding a new bottom. The ship’s machinery (an inverted direct acting engine rated at 140hp) was serviced and re-certified at the same time. Lady Darling’s net tonnage was raised (reflecting its additional length) to 895 tons.

For the next four years, the Lady Darling operated in the Mediterranean and on the Atlantic crossing between England and Canada before being sold again in 1875 to James Paterson of Paterson and Company, Melbourne, Victoria. Upon the steamers’ return to Australia, it was promptly put back onto the Melbourne–Newcastle–Melbourne route as a collier with a 1000–1200 ton cargo capacity.

On its final voyage in 1880, the Lady Darling departed Newcastle, New South Wales – on its regular run to Melbourne – with 1220 tons of coal on the 8th November and then proceeded to steam and sail its way down the New South Wales coast, battling a rising gale.

The steamer was off the South Coast of New South Wales, approximately four nautical miles south of Montague Island, in the vicinity of Aughinish Rock, in the late evening of 10 November 1880 when Captain Roberts reported that the ship had struck something: ‘abreast the engine room and nine feet (2.75m) below the water line and forty feet (12.2m) forward of the stern’.

The impact tore upon the coal bunkers near the engine room’s aft bulkhead, opening the hull to the sea, which quickly flooded the engine room putting out the fires and making the ship’s pumps inoperable. Unable to manoeuvre, with its pumps out of action and the hull rapidly filling the Captain and crew abandoned ship. The crew made their way towards Montague Island where they were assisted by the construction crew employed at building the new lighthouse on the Island.

On the morning of 11 November, the crew of the Illawarra Steam Navigation Company’s steamer Kameruka located the remains of the sunken vessel south-west of Montague Island in 15 fathoms (28 metres) of water and subsequently reported their discovery to the Marine Board in Sydney. The Marine Board promptly despatched the pilot vessel, Captain Cook, to investigate the discovery and rescue any survivors.

At the Court of Marine Inquiry, held in late November 1880, neither the Captain, Deck Officer nor any of the ship’s crew reported seeing any reef or floating debris either before or after the vessel struck. With no evidence to indicate otherwise the Court found that no blame could be attached to the Officers and crew of the ship as the vessel appeared to have struck an unidentified object such as a piece of wreckage or an uncharted reef.

The actual location of the Lady Darling remained very much a mystery until August 1996 when the net from a Bermagui fishing trawler, operated by Dom Puglise, became entangled on something on the seabed off Cape Dromedary. Puglise asked Bert Elswyk, the owner of a local fishing and dive charter boat, and his friend Paul Mood to recover his snagged nets. On the 16 August 1996 Elsyck and Mood dove on the spot indicated by Puglise and in doing so found that the nets had snagged on the remains of Lady Darling’s iron hull.

Due to its historical and archaeological significance, the Lady Darling now lies within a Historic Shipwreck Protected Zone and the site has the highest level of protection under the Historic Shipwrecks Act (1976) only accessible through a permit system issued by the Federal Minister for the Environment or their State delegate.

The wreck today

Recently the Maritime Archaeology Research Centre (MARC) at the Australian National Maritime Museum obtained such a research permit to enter the Protected Zone around the Lady Darling to conduct a 3D mapping exercise on the wrecksite.

Taking advantage of predicted favourable light westerly winds and opportune tides the dive team, consisting of Lee Graham, Dr James Hunter and Kieran Hosty from the MARC, Paul Hundley from the Silentworld Foundation and two volunteer archaeology divers Matilda Goslett and Eliza Goslett, arrived in Narooma, on the south coast of New South Wales, some 350 kilometres south of Sydney in early August 2016.

After talking to the Narooma Coastal Patrol, who would be supplying safety radio cover during the fieldwork, and assessing the area’s various boat ramps, the team launched Maggie III and prepared to dive what is considered to be the most intact shallow water shipwreck (less than 30m) in New South Wales waters.

Maggie III, the team’s research vessel (provided by the Silentworld Foundation) first had to successfully cross the infamous Narooma Bar at the mouth of the Wagonga Inlet. After assessing the Bar and checking in with the Coastal Patrol, our dive team departed Narooma for the 14 kilometre trip to the wrecksite – which is located 5.5 kilometres south-west of Aughinish Rock, 8 kilometres south-west of the southern end of Montague Island (home to a large permanent colony of Australian and New Zealand Fur Seals) and two kilometres offshore from Mystery Bay (Cape Dromedary).

Arriving on site we first located the wreck by using a combination of GPS co-ordinates and Maggie III’s side scan sonar. Once located , as we could not anchor on or near the wreck in case we damaged it, we then rigged up a shot line which would guide our divers down to the seabed.

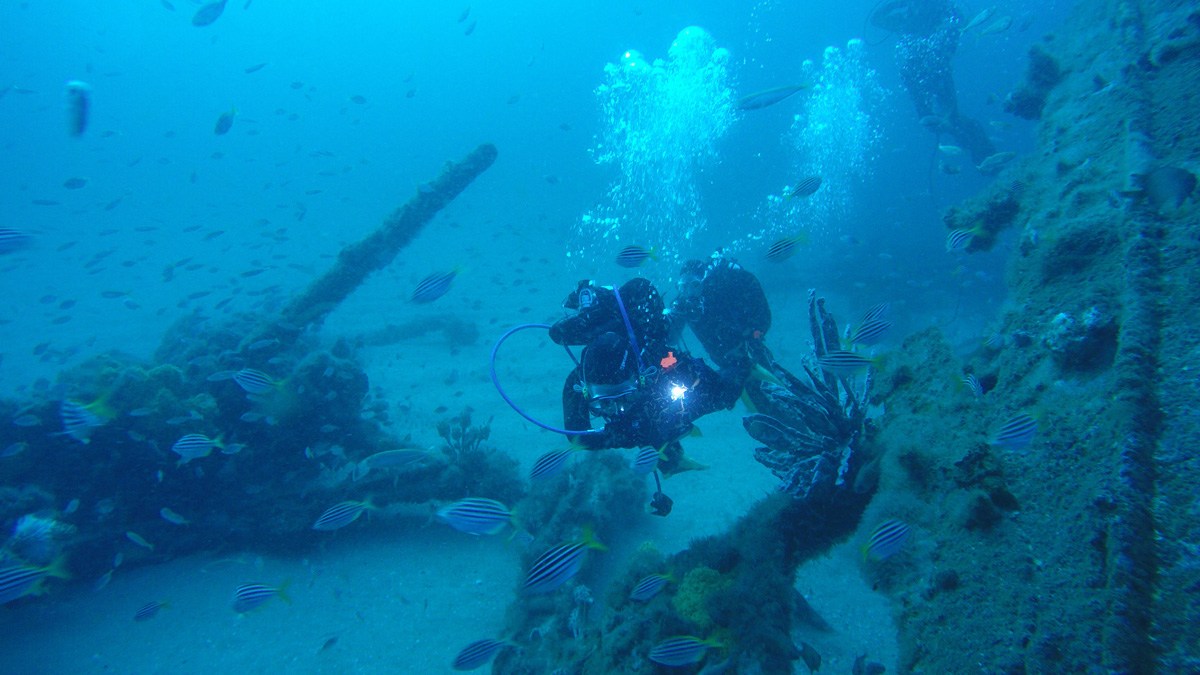

Following final safety briefings the dive teams entered the water and swam down to the wreck which slowly appeared resting on a relatively flat sandy bottom in 29-30 metres of water. With a slight current pushing us southwards we quickly found the relatively intact counter stern of the Lady Darling (reinforced by structural sound iron cant frames), bilge stringers and a transverse bulkhead. The structure rises up some 4 to 5 metres off the sand and supports the remains of the upper deck (minus its timber decking) as well as the steamer’s large steering quadrant.

Moving forward of the transverse bulkhead, and swimming between the port and starboard hull plating (which projects between 1 and 2 metres above the sand), we swam over what was Lady Darling’s engine room. We could see the steamer’s exposed propeller shaft, massive twin cylinder, vertical, inverted, direct acting steam engine (230 cm long x 400 cm high) as well as an equally impressive large, single cylindrical type, ship’s boiler (325cm long x 320 cm wide), lying just aft of another transverse iron bulkhead.

SS Lady Darling site. Image: John Riley Memorial Collection, Heritage Branch, Department of Environment and Heritage.

Forward from the engine room’s bulkhead, we swam over the remains of the steamer’s cargo holds, which would have originally contained more than 1200 tons of Newcastle coal. In this section of the wreck, the sides of the steamer’s hull (unsupported by the transverse bulkheads) have collapsed outwards. They are almost level with the surrounding sand and the coal has become dispersed by the strong currents which frequent the site.

In the past, this area of the wreck has been deeply buried in the sand for some 30 to 40 metres before protruding again and rising up to the bow section. However, on our recent visit the entire forward section of the ship’s hull, including its iron keelson, lower iron floors and water ballast tanks were lying exposed on the seabed, with the port and starboard sides of the hull splayed out on either side. Lying on top of the exposed lower deck plating were the remains of the ship’s upper deck. These consisted of iron deck beams supported by tie plates, diagonals and the mast partner plates, that reinforced the main and fore masts of the Lady Darling.

Off to starboard we also observed a small upright donkey boiler, which would originally have supplied separate steam power to deck winches, pumps and windlasses.

The intact bow is now home to small shiver (or group) of Port Jackson sharks. The bow is tilted over on its starboard side and all the fittings associated with the bow, including Admiralty and Porters Patent anchors, a capstan, a davit and anchor chain, have tumbled outside the hull and now lie on the seabed to the west of the wreck.

With our initial inspection over it was down to business. Along with the sounds of passing humpback whales singing in our ears and being occasionally photobombed by a curious New Zealand fur seal, we commenced recording the wreck. We used two GoPro cameras which were equipped with a variety of coloured filters to help compensate for the effect of water depth. The density of the water effects the ambient colour spectrum and is one of the big problems with taking underwater images at such depth. Colours such as red disappear at around 5m, orange at around 8m, yellow at around 12m and green at around 22m – turning the underwater terrain into murky blues and browns.

Archaeological diver Matilda Goslett with a GoPro camera equipped with colour correcting filters. Image: ANMM.

Working quickly in two teams, we recorded the major structural features such as the bow, counter stern, engine, boilers and transverse bulkheads allowing for up to 40% overlap between each set of images. Unfortunately, at 30m you don’t get much safe bottom time before you start incurring a serious decompression commitment so after 20 minutes on the bottom it was time to ascend the shot line and commence our various safety stops before being picked up by Paul Hundley and Maggie III circling above us.

In the afternoon the same process was carried out but with an even shorter bottom time of 15 minutes. However, practise makes perfect and with no need to carry out a site inspection on our second dive, we managed to record a significant area of the wreck before we once again had to make our ascent to the surface.

Now back in Sydney, the team are currently assessing the still images and digital footage obtained on our two-day site inspection of the Lady Darling shipwreck and we’re running the images through the AgiSoft software to create the 3D map of the site. Stay tuned for future blogs detailing our progress.

—Kieran Hosty, Manager of Maritime Archaeology

You can find out more about the museum’s maritime archaeology initiatives at our website and on our blog.

Acknowledgements

- Paul Hundley, Silentworld Foundation

- Eliza Goslett, Volunteer Archaeological Diver

- Matilda Goslett, Volunteer Archaeological Diver

- Giada Smorto, Liceo Scientifico Statale, Rome, Italy

- Ross Constable and Bronwyn Roll, Narooma Coastal Patrol